It should come as no surprise I decided to watch AMC’s latest foray into westerns, Hell on Wheels, the minute I saw Anson Mount smoldering his way across the trailer. Oh my preciouses! The long! The lean! The shoulders and steely-eyed glare! His ex-Confederate soldier Cullen Bohannon is such a fine piece of man flesh, even the beard and a permanent layer of grunge can’t detract from his lickaliciousness.

Likewise, since I’m a writer, it should come as no surprise that I immediately followed my first viewing of the show with an orgy of research into the series, its setting (the laying of the First Transcontinental Railroad), the critical reaction… And that’s where I stopped, because the first review I read turned out to be an extended rant on how the show wasn’t true to the period, because it insisted on shoe-horning modern attitudes and issues into the history of the period (italics mine).

Hell-o! That’s what historical fiction does. No historical fiction (or nonfiction, for that matter) depicts a period or its issues accurately in context for the same reason you never step in the same stream twice. Not only has the United States changed since the mid-nineteenth century, we’ve changed. You couldn’t create a leading man—or leading lady—true to 1865’s ideals without producing 2012’s idea of a monster.

Regardless of whether he fought for the North or South in the Civil War, the ideal 19th century American male would be a white supremacist. He would be narrow-minded with respect to religion, whatever his religion happened to be. He’d consider women creatures of inferior intellect and “moral fiber” who needed to be “protected” and segregated for their own good, like children and other feeble-minded souls: African-Americans, Native Americans, Latin Americans, Asians, Africans, the Irish, the Italians… His sense of entitlement would make the top management of Lehman Brothers seem morbidly self-abnegating by comparison. And the less said about his dietary expectations and personal hygiene, the better.

The ideal woman of the time would not only share his attitude, she’d conspire with her beloved to enforce the oppression of her peers. If those less perfect vessels complained, they’d be dismissed as bitter shrews with a persecution complex. Chances are the description would be accurate, too. Sustained repression, the total absence of rights and an inability to rectify the situation will do that to a girl.

But that’s okay. The creators of Hell on Wheels and Samhain’s many fine historical novelists don’t have to create nineteenth century beau ideals. They’re not writing for 1865. They’re writing for now. So they create characters who don’t fit in their time, like a failed southern tobacco planter who married an abolitionist (Bohannon); a half-black, half-white former slave; an aristocratic Englishwoman in search of an identity outside of the expectations of her class; a prostitute tattooed (mutilated in the view of the time) by the Native American war band that abducted her as a child; and an entrepreneur determined to grind into dust all those who despised him for being born poor and Irish-American (see the nineteenth century opinion of Irishmen two paragraphs above).

The characters’ inability to blend in forces them to become agents of change—bridges between their time in history and ours. They allow us to congratulate ourselves on how far we’ve come and to view their challenges as a measure of how far we need to go.

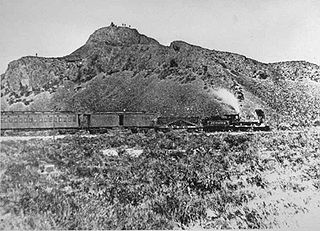

This doesn’t give creators of historical fictions—literary or video—a pass on getting the details right. Heaven help the producer whose audio effects person uses a diesel whistle for a steam train, for example. About three million locomotive enthusiasts and (in the case of my husband) their immediate relations will flood their offices with irate letters, emails and phone calls. Period details aside, the success of any historical fiction depends on its ability to speak to the people of 2012 and those who come after. And the way you speak to us is to address our meaningful issues and conflicts, whether it’s government malfeasance, corporate greed, class conflict, race relations, gender issues or notions of romance.

This use of the myths, legends and histories of the American West isn’t anything new. The First Transcontinental Railroad has long been viewed as means to examine our national goals. Among the movies and TV shows which use it for this purpose are John Ford’s silent film The Iron Horse, Cecil B. DeMille’s Union Pacific and multiple episodes of the TV series Maverick. There’s also Jules Verne’s ironic take on the whole business in Around the World in Eighty Days. Even better to my mind, however, is Hell on Wheels’ most illustrious predecessor: Mel Brooks’ 1974 classic, Blazing Saddles.

You don’t see the resemblance? There’s corporate greed and governmental incompetence, a serious examination of the many forms of bigotry, professional ladies with accents, a smart-mouthed African-American with an agenda, and a bad-assed gunman with a tragic past. Of course, that makes railroad entrepreneur Thomas Durant (played by Colm Meany) 2012’s Hedy—I mean Hedley Lamarr, and turns Gene Wilder’s Waco Kid (sporting his Donald Trump comb-over) into my boy Bohannan…

What? Yes, I can see how you’ll never be able to view the series in the same light ever again. No, of course, I won’t stand in your way if you need to bleach your brain now.

You’re welcome.

(Originally published in the blog of Samhain Publishing, Ltd., January 2012)